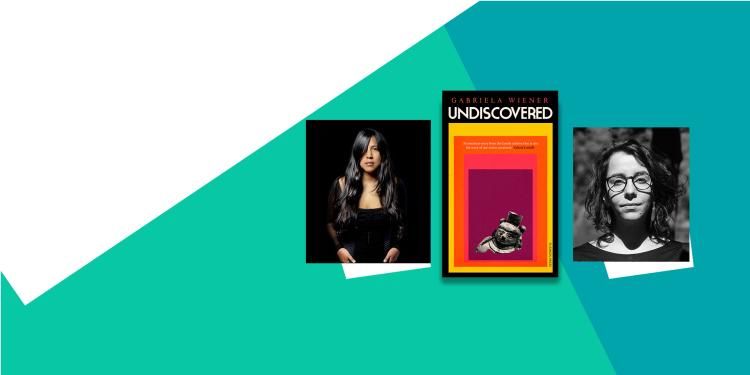

A Q&A with Gabriela Wiener and Julia Sanches, author and translator of Undiscovered

With Undiscovered longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024, we spoke to its author and translator about their experience of working on the novel together – and their favourite books

Read interviews with all of the longlisted authors and translators here.

Gabriela Wiener

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024, and what would winning the prize mean to you? Would it also have an impact on literature originating from your country?

It’s funny – lots of people have asked me that question since the announcement, and there’s only one answer I can give. Aside from pride, delight and gratitude, the sentence that keeps running through my head and sums up the feeling best is: Here I am, I exist, my writing exists, I’ve finally been seen, I’m finally going to get some respect. It hasn’t been easy, being a woman writer, and much less a non-white woman writer who makes a claim for personal experience, for a political perspective and a body of knowledge which aren’t academic, or otherwise represented in literature. And even less easy has been doing it as a writer from the Global South, a migrant to Europe, who also practises journalism and speaks her opinions aloud. Ostracisation, harassment and attempts at silencing are the order of the day. And the lack of respect, always a lack of respect.

So I think if I won the prize, it would mean something not just to me but to many migrant, racialised women, especially for those of us who come from the former Spanish colonies – the Indians, the ‘noble savages’, so often handled with an infinite, excruciating paternalism, never treated like the creators of other possible worlds. It would mean that we’re here, that we exist, that we’re seen, that we’re finally respected. In Peru there are mestiza women writing, indigenous women, Quechuas, Aymaras, women from the Amazon, though not many people are talking about them. Many of them suffer from rachismo – when racism and machismo fall on you with a double force. I write with those women at my side. Power cannot tolerate resistance, because it’s an affirmation of the lives it has tried to destroy; power didn’t expect us to survive but now we’ve come close to winning a Booker.

What were the inspirations behind the book?

Undiscovered draws from the sources of folk and revolutionary art, mestizo literature, antipatriarchal, indigenist literature, from voices that subvert the social order to raise themselves up, from my migrant community. Everything that contaminates, subverts and bastardises the known paths, and opens others, everything that shares, that gives of itself, exchanges and offers itself freely, interests me.

Through the rewriting of personal, intimate, familial, social stories I’m trying to recover a lost memory. The writing of fiction, the literary imagination, becomes a way to complete these broken memories for the people who have remained outside of official History, the archival record, those who don’t have birth certificates, or surnames, or family crests – and a way to dream of another future. To look for the first time at the reality of colonial, racist, classist violence in our own era. I think we’re lucky to live in a moment of resurgence for folk art, antiracist, feminist, indigenous art, art inevitably shot through with activism and political struggle. We’re making books that are also political and artistic movements. Avant-garde art is social and shows us the path toward transformation, it’s not an island where artists withdraw from the world in order to create. Violeta Parra, Pedro Lemebel, Ana Mendieta, whom I look to as loving ancestors, created from experience and the body, they sang, they performed for the people and against all forms of supremacy.

Gabriela Wiener

What made you want to tell this particular story?

Being an unintegrated migrant in Europe, forming part of a community movement which is critical of our host country, assembling our list of demands for justice, memory and reparation. And doing it from my world, in my language and in the most entertaining way possible. I realised that this was my subject and my conflict in the present, but that at the same time it was a problem that came from long ago, a conflict that runs through my entire body, from north to south, with everything on the line: my origin, my identity, my family history – and that it wasn’t just happening to me, that being the bastard mestizo offspring of violence made sisters of us, and that speaking it, writing it made us look dangerous, transformative. I was spurred on by the idea of politicising the pain of the diasporic experience, to find what to do with that wound and to avoid forgetting. History is the story of power. And for a long time they’ve been telling us that version, and we’ve swallowed it. I was driven to create a story that would be a counterweight.

How long did it take to write the book, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

Undiscovered is a kind of book made of books – there are three partial novels that converge in a single volume. The ancestral novel, the novel about the unfaithful father, and the novel about the polyamorous girl don’t exist, but they ended up weaving together across the past decade to form this book. Some of the essayistic sections of the book had a previous life as ideas, disparate posts, newspaper columns. More than manuscripts or drafts, there were fragments of me that I devoted myself to gathering up and assembling into a whole, pieces of a patchwork, like those blankets our grandmothers used to make with scraps, something I finished sewing into shape in a year of writing and rewriting. There was no prior plan, I arrived at it in the end, surprised as though at a revelation of what I could say and do. I realised that these texts where part of a single literary and imaginative system.

I write with a laptop lying on my stomach in bed, working or going back to sleep as fancy or disenchantment take me. I’m a freelance writer, I live and eat and take care of my children with what I’m paid for my writing, I’m not a romantic with a room of my own, I don’t have one, nor do I have years to spare for revising my next novel. I have a journalist’s habits, I’m used to operating under pressure and on a deadline.

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Julia, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

It was a close collaboration, she sent me emails with her queries and I resolved them. It was a very dynamic and fluid process, as though we had met in person, though we still haven’t. I particularly remember when it came to translating the poem within the novel, ‘Panchiland’, I was surprised and delighted that she decided to take inspiration from the tradition of spoken word. She did a masterful job.

I was spurred on by the idea of politicising the pain of the diasporic experience, to find what to do with that wound and to avoid forgetting

Tell us about your reading habits. Which book or books are you reading at the moment, and why?

I read in a kind of applied way, so at the moment, for example, I’m reading about the Russian Revolution, an instructional book written by an imprisoned Peruvian ex-guerrilla, I’m reading Lenin, the Marxist Peruvian thinker José Carlos Mariátegui, and the novel cycle La guerra silenciosa by the neoindigenist Peruvian writer Manuel Scorza. All of this because I’m writing my big Russian novel: the story of how a leftist leader is made and unmade, from his education in an indigenist Soviet school in Peru in the 1980s, up to the present day when he’s in jail because of lawfare.

I’ve also just finished reading the most recent books of two Ecuadorian writers whose work I really value: Mónica Ojeda, Chamanes eléctricos en la fiesta del sol, and Mafe Moscoso’s La Santita. They’re both powerful poetic immersions in the Andean universe, written by two brilliant migrant authors.

What was your path to becoming a reader – what did you read as a child and what role did storytelling play in your younger years? Was there one book in particular that captured your imagination?

My route was poetry. Above all I read poems by César Vallejo, but also other poets from my country, Javier Heraud, Alejandro Romualdo, Juan Gonzalo Rose. In terms of narrative, I read the classics in children’s editions: Vallejo’s Paco Yunque, Edmondo de Amicis’ Heart, David Copperfield by Charles Dickens, Uncle Tom, etc. At 12 I was stunned by One Hundred Years of Solitude – so sensual, full of laughter, exuberant.

Tell us about a book that made you want to become a writer. How did this book inspire you to embark on your own creative journey, and how did it influence your writing style or aspirations as an author?

When I was a girl my parents gave me Spain, Take this Chalice from Me, the poetry collection that César Vallejo was moved to write by the horror of images of the Spanish Civil War. The book included photos of children killed in the war, shot in the head. It was impossible to read those poems, aged 10, and not be marked by the writing with its human and political resonance, as well as its exacting, avant-garde approach to language. I still know it by heart: ‘Niños del mundo, si cae España, digo, es un decir, si cae España su antebrazo que hacen en cabestro dos láminas terrestres, niños qué edad la de las sienes cóncavas, qué temprano el sol que os decía, qué pronto en vuestro pecho el ruido anciano, qué viejo vuestro dos en el cuaderno’.

But I would say generally that I wanted to be a writer after reading all of César Vallejo’s poetry. Beginning as a reader with Vallejo is like the first thing you eat being Peruvian food – afterward everything else tastes bland. When I started reading, I also started giving recitals of Vallejo poems at school. My relationship with literature has always been oral and performative. I discovered myself as a storyteller by regaling my girlfriends with my wild adolescent exploits. They loved them, but when I’d tell my boyfriends the opposite happened, they felt insecure, jealous – one of them even hit me after listening to my stories.

Tell us about a book originally written in the language in which you write that you would recommend to English readers. How has it left a lasting impression on you?

Deep Rivers, by José María Arguedas, which I read as a girl, and which kept me company while I wrote Undiscovered; I was marked by its Andean lyricism, its mestizo pain, its cosmic Quechua vision. Arguedas is one of those writers whose amazing work was eclipsed by a writer like Vargas Llosa, who for many years has been almost the only representative of our literature. The truth is, it’s much more diverse.

Do you have a favourite International Booker Prize-winning or shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

No, what I have is a burning desire to read them!

What role do you think translated fiction plays in promoting a more inclusive and diverse literary canon, and how can we encourage more people to read it?

Its role is fundamental. The prestige that translated fiction acquires after being listed for, say, the International Booker Prize is significant. Big and small publishers, prizes, academia and other first-world institutions carry a huge responsibility, at a time when there are forces across the continent trying to persecute diversity and force inclusion backwards. I believe that a new canon could help literature stop seeing itself exclusively as a club which reserves the right of admission, as an activity pursued only by married white men, solitary geniuses or white women with rooms of their own, illustrious, metropolitan authors of the Global North, writing exclusively about their experiences, dramas and obsessions. Other stories are being told, or are there to be told, from other points of view, and they deserve to be known and recognised.

This kind of nomination can also be, for these other authors, the first time that literature presents itself to them as a paid job, from which they can carve out a trajectory that will have an impact on their communities of origin. Now, it’s been awhile since these communities stopped knocking at the door, they’re no longer asking for favours or permission. There’s no longer any need to do something for them, just to watch them do it for themselves. More and more, I see that they don’t want to go where they’re not wanted. They might just decide to set up camp outside the universal canon – or to batter the door down one day.

Julia Sanches

How does it feel to be shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024 – an award which recognises authors and translators equally – and what would winning the prize mean to you?

I am delighted that this dark horse of a novel (to quote our US editor, Alfredo Fee) and its brilliantly outspoken author are getting a moment in the spotlight. The conversation that unfolds in the pages of Undiscovered is as necessary today as it ever was. What would winning the prize mean to me? Let’s not jinx it.

How long did it take to translate the book, and what does your working process look like? Do you read the book multiple times first? Do you translate it in the order it’s written?

I can’t remember for the life of me how long it took to translate this book. Every project feels a bit like a fever dream. A month, two? My entire life?

My working process varies from book to book. Sometimes I read the book before I start translating it, sometimes I don’t. And the reason for this is very prosaic: time, deadlines, an attention span that has been impacted by COVID and my smartphone.

Though I usually translate from start to finish (as I did with Undiscovered), the last book I translated, Geovani Martins’ Via Ápia (working title), was done by character. The book follows a group of four, young, male friends in Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro, the largest favela of Latin America. Every chapter, with few exceptions, is told from the point of view of a different character. I was worried the voices would blend together and become indistinguishable if I didn’t pull them out and translate them in blocks, so I colour-coded the PDF, wrote every chapter heading in my working document, and forged ahead. It was an interesting, if disorienting, experience as I completely lost my grasp on the chronological order of events. I’m not sure I’ll be doing that again…

Aside from the book, what other writing did you draw inspiration from for your translation?

I usually read companion texts to the books I translate, listen to companion music, consume companion media. TV can be very helpful (don’t judge). I can’t remember where exactly I drew inspiration from for this translation (it was a long time ago, and my memory is a sieve), but if I were to do this over, I’d say: Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, Safiya Sinclair’s Cannibal, Micaela Coel’s I May Destroy You, and the Chilean musician Ana Tijoux.

Julia Sanches

As a Brazilian who grew up all over Europe and the Americas – in the U.S., Mexico, and Switzerland, to name a few – I have never not been a translator, if translating means refashioning an experience in another language

What was your path to becoming a reader – what did you read as a child and what role did storytelling play in your younger years? Was there one book in particular that captured your imagination?

I remember, shortly before my family moved from the United States to Mexico, that my teacher and classmates gave me a copy of Roald Dahl’s Matilda. They’d all signed it, wishing me the best, I assume; I’ve lost that book since. Let’s say that book captured my imagination, much as I have almost no recollection of the experience, if only because it makes for a good story.

My grandfather, on my mother’s side, was a great storyteller. In Brazil, he would devise treasure hunts that would take us into the thick of the rainforest and then out onto a rock on the edge of the ocean. He’d point to vultures circling above an island and tell my cousins and me that they were Peter Pan’s Lost Boys. He’d terrify me with tales of a woman who’d been buried alive…

Tell us about your path to becoming a translator. Were there any books that inspired you to embark on this career?

As a Brazilian who grew up all over Europe and the Americas – in the U.S., Mexico, and Switzerland, to name a few – I have never not been a translator, if translating means refashioning an experience in another language.

At school, I wasn’t taught to read translations in a way that considers the translator as part of the aesthetic experience (I don’t think many people are), so I only realised literary translation was something people did when I encountered a translation that wasn’t especially good. It’s when I noticed the power of a translator’s choices. Then I started tinkering, at first with poetry. The rest is history. (I do wish my origin story as a translator didn’t involve reading a bad translation. Maybe I should make up a new one.)

What are your reading habits under normal circumstances? Which book or books are you reading at the moment, and why?

What are normal circumstances…?

The way I choose what to read is half haphazard, half very intentional. The intentional part has to do with what I’m translating. As I said above, I read a lot of companion books to my translations, which can take me to unexpected places (but also takes up a significant portion of my reading time).

I am one of this year’s judges for the National Book Award, so right now I am reading for that, which means I can’t talk about it. (Picture me winking.)

Tell us about a book originally written in the language from which you translate that you would recommend to English readers. How has it left a lasting impression on you?

I translate from three languages that are spoken by close to 500 million, so it’s kind of hard to narrow it down, but I always find myself going back to Clarice Lispector’s stories. As a reader, I don’t care much for plot. What I’m interested in is seeing the ordinary in a completely new, unusual light. And this is something that Lispector excels at.

Which work of translated fiction do you wish you had translated yourself, and what aspects of this particular work do you admire most?

Pilar Quintana’s The Bitch. The way she is able to create atmosphere, foreboding, out of so little… (Lisa Dillman’s translation is flawless, just to be clear.)

Do you have a favourite International Booker Prize-winning or shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

Raduan Nassar’s A Cup of Rage. It’s a slim, fireball of a novella. So much energy and intensity packed into, I believe, eighty pages… The translation is astonishing as well.

What role do you think translated fiction plays in promoting a more inclusive and diverse literary canon, and how can we encourage more people to read it?

Translated fiction is a fact of literature. Not reading it is like depriving yourself of the vast majority of the food pyramid. A canon without translated literature is undernourished. Anemic. It has scurvy. A vitamin-D deficiency. You get the idea. I can’t wait until we don’t have to ask or answer this question anymore.

(I should note that it’s only English readers who need to be encouraged to read translated literature. Readers everywhere else read books translated from other languages without having to be cajoled.)

- By

- Gabriela Wiener

- Translated by

- Julia Sanches

- Published by

- Pushkin Press